Today, I would like to share a clinical case (with the patient’s consent and thanks) involving post double eyelid surgery ptosis, medically known as blepharoptosis.

The patient previously underwent cosmetic double-eyelid surgery at another clinic. Although she had natural double eyelids initially, a slight fullness from eyelid fat was apparent. After the previous surgery, the patient developed a noticeable drooping of her upper eyelids (ptosis), as shown in the first image. The performing surgeon suspected myasthenia gravis and prescribed Mestinon, but the drooping did not improve suggesting a different cause. The patient experienced significant emotional distress due to facial changes and multiple side effects from the medication, prompting referral to a neuro-ophthalmologist. After comprehensive testing including blood work and muscle evaluation it was concluded that her ptosis was most likely a consequence of her prior eyelid surgery, not a primary muscular disease.

How Can Double Eyelid Surgery Cause Ptosis?

Overly aggressive fat removal or repositioning, combined with suturing the eyelid crease too high, may lead to the formation of scar tissue that adheres to the eyelid elevator muscles. This scarring can restrict eyelid elevation, resulting in iatrogenic ptosis, or “surgical-induced drooping” of the upper eyelid

What Is Ptosis?

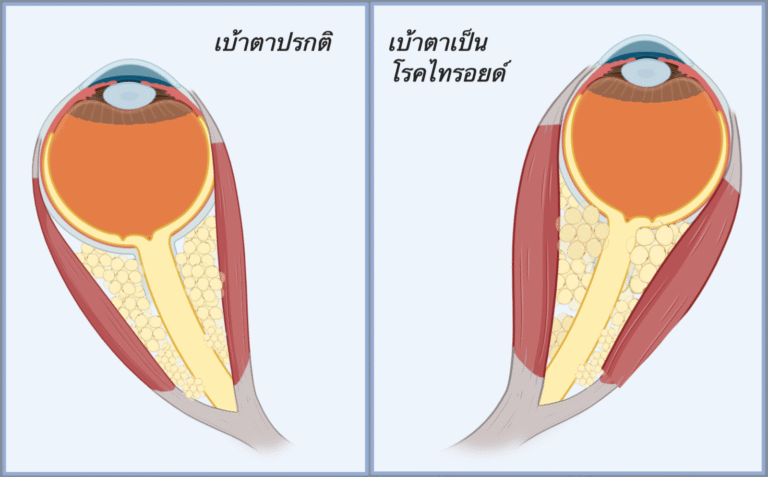

Blepharoptosis (ptosis) is the abnormal drooping of the upper eyelid beyond its normal position. Typically, the natural upper eyelid margin lies approximately 1–2 millimeters below the superior corneal margin. When the eyelid descends significantly beyond this range, it may partially obstruct the upper visual field. Patients often subconsciously compensate by arching their eyebrows resulting in forehead wrinkles or tilting their head upward to improve vision.

How Is Ptosis Evaluated?

When evaluating eyelid ptosis, the physician measures the distance between the upper eyelid margin and the center of the pupil, as well as the strength of the eyelid-lifting muscle, known as the levator muscle function. This is tested by asking the patient to look down and then up repeatedly, while the examiner blocks the eyebrows to prevent compensation. The results are recorded in millimeters.

In normal individuals, levator function measures greater than 10 mm. In patients with muscle weakness, the value is typically below 10 mm. In cases of congenital ptosis, the function may even be 0 mm, indicating no lifting power at all.

Common Causes of Ptosis

Most patients who present with eyelid ptosis do not suffer from true muscle weakness. In fact, the majority still demonstrate normal levator function. The drooping often results from levator muscle dehiscence or laxity, commonly caused by aging or habitual behaviors such as frequent eye rubbing in patients with ocular allergies, In contrast, congenital ptosis is typically due to underdevelopment or atrophy of the levator muscle itself, which may be considered a form of true muscle weakness.

In summary, the common causes of eyelid ptosis can generally be classified into four main categories:

- Aponeurotic Ptosis Often age-related or linked to repetitive eyelid rubbing, leading to detachment or loosening of the levator aponeurosis. **Most common

- Myogenic Ptosis Due to underlying muscular disorders like congenital ptosis, myasthenia gravis, or muscular dystrophies.

- Neurogenic Ptosis Caused by nerve dysfunction, such as third cranial nerve palsy or Horner’s syndrome. (Less frequent)

- Mechanical Ptosis Resulting from physical weight or masses on the eyelid causing it to droop. (Also less frequent)

How is ptosis surgically corrected?

There are several surgical approaches and techniques, depending primarily on the levator muscle function. If the levator muscle demonstrates normal function—as in this patient’s case—the procedure involves tightening and repositioning the levator muscle to restore the eyelid to its proper position.

Since this patient had previously undergone double-eyelid surgery with a very high eyelid crease, the operation also required revision of the crease by releasing old scar tissue. In addition, abdominal fat grafting was performed to cover the levator area, preventing future scarring and abnormal adhesion.

This case represents one of the more challenging types of ptosis surgery, requiring advanced oculoplastic surgical expertise. (Postoperative photo at 2 months shown below.)

Pimkwan Jaru-ampornpan, MD

Assistant Professor and Chief of Oculoplastic Service, Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital